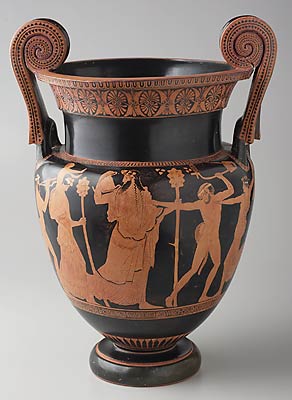

The Greek krater soon to be leaving the Minneapolis Institute of Arts for Italy

Last week it was announced that the Minneapolis Institute of Art would be returning a 5th Century B.C.E. greek vase, a volute krater, if one wanted the be precise, to Italy where it evidently originated.

The Minneapolis art museum obtained the vase in 1983 from a prominent antiquities dealer in Europe who, it turns out, has been also connected with some of the objects that the Getty had troubles with. By the standards of the time, the Institute says, the provided provenance of the vase passed muster, but that was a time where the issue of trade in looted artifacts wasn’t under the scrutiny it is today. The vase in Minneapolis has been identified as the same one in photographs ceased during a 1995 investigation by Italian authorities into archeological looting. The Minneapolis Institute of Art is thus returning the item to Italy, but has not been accused of any wrongdoing.

But is this a wise, good, or even ethical move on the part of the museum?

There have been many nations that have been pursuing the return of various artifacts to their own countries. There is the case of the Euphronios krater returned to Italy by the Metropolitian Museum of Art, where it resided from 1972 onward. (Interestingly, there are names in common between the Met’s former krater and the one in Minneapolis.) Egypt has also demanded various artifacts be returned to their country, sometimes using fairly hardball tactics. The Egyptian wish list includes such notable items as the bust of Nefertiri in Berlin’s Neues Museum (and which has been in Germany since 1913, a year after it’s discovery), and the Rosetta Stone, which has been in the British Museum since 1802. And, of course, no such list would be complete without the Greek claim on the collection of Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum (known as the Elgin Marbles).

Looting of archeological sites is a very real problem. It should be taken seriously by authorities with jurisdiction over such sights and those who carry out the practice or direct it should be prosecuted and subject to significant penalty. It is important to protect the world’s heritage and history against those who would so often destroy valuable information and artifacts in order to get at a few spectacular ones that might fetch a hefty price on the antiquities market. Museums should certainly be careful about checking the provenance and authenticity of the items they collect. But…

But, I do not know that it then follows that the looted objects should necessarily be returned to their country of origin. These things aren’t just treasures of one particular nation, but treasures of world culture. The rhetorical logic of some of these sorts of claims leads ultimately to the idea that the products and artifacts of that culture should only be found in their homeland. If one wants to see Egyptian artifacts (or at least ones of particular beauty, quality, or importance) one would need to go to Egypt. If one wants to seek Greek statuary, Greece. It’s rarely taken to such ends, but there is no clearly articulated ending point here. It is suspicious that objects just a few centuries younger don’t seem to be under the same preasure. When does such a preference toward repatriation end? Or how far back does one allow claims to go? Would it be appropriate for Turkey to demand Venice return the Quadriga that once adorned St. Mark’s Cathedral, since they are artifacts of the ancient Roman empire taken from Constantinople as spoils of the crusades? How appropriate would it be for Egypt to demand the return of an obelisk that has been in Rome since the Roman Emperors moved it there? I wouldn’t expect the authorities and advocates arguing for various artifacts to be repatriated to make a clear definition of what the edges of their arguments really are. It wouldn’t suit their purposes and desires, for it could give a real test of a particular claim and aid an argument for a different principle or perspective.

With the Elgin Marbles and the Rosetta Stone, for instance, these are items that have been in a particular museum for the neighborhood of two centuries now. The historic collection of the British Museum is itself a historical artifact. The collection of objects there were influential on culture, art, literature, history, and, yes, even the study and development of archeology. It can be argued (correctly, I believe) that keeping this collection together is itself an important matter in the preservation of the world’s heritage and history, even if many of the artifacts came into that collection under circumstances that would not be tolerated today.

But could it not be that more recent acquisitions of questionable origins present a different matter? In some cases, certainly. But on basic principle? I’m not so sure.

Surely questions of an objects origins might prompt questions of where the object belongs, but it shouldn’t be the deciding factor. The question of the museum’s conduct here must play a role. If the museum was encouraging illegal trade and archeological looting, or intentionally turning a blind eye to irregularities (as it appears the Getty had done with numerous objects in its antiquities collection), that is one matter. A museum and the responsible individuals should rightly be held accountable, including the required return of an object to its home country. But what if the museum acted appropriately according to the standards at the time of the acquisition? Then I say the institution should be held harmless, including retaining possession and ownership of the item. There is a need to discourage looting. Museums play a role in preventing the destruction of our human heritage by seeking only to obtain art that’s not being sold after it was looted or stolen by doing the appropriate research into the object. But the onus should lie mostly on authorities to prevent looting in the first place, and fully investigate and prosecute those who loot, steal, and fence such material.

Which leads me back to the Minneapolis volute krater. The Euphronious krater (the object formerly at the Met in New York) is apparently a spectacular object (I’ve never seen it) and I expect it would be a centerpiece of any collection of ancient Greek pottery. It is understandable that Italy would be eager to obtain it. But the Minneapolis vase, while quite nice, does not appear to be of that calibre. I fear it will go back to Italy to molder on a storage shelf with a great many other similar objects, or to be lost in a too large museum display of many others, only to blend in to what looks like endless repetition to anyone but a scholar in such objects. Meanwhile, in an institution like the Minneapolis art museum, it would be an object enjoyed and treasured. This, I think, matters a great deal.

Art is not meant to be put into a storage vault. Art is meant to be displayed, looked at, considered, to educate, to be admired, and enjoyed. That’s true if the object is a beautiful painting, fantastic sculpture, or an ancient everyday object that gives us a glimpse into life or a people’s practices and values in it’s own era. And, I would assert, art is more valuable on display in a collection where it more clearly illustrates or communicates, where it more clearly shines, than in a collection where it gets lost amongst a display of many other objects. This because it more clearly fulfills its position of bringing beauty, meaning, a glimpse, or simply joy than when it is lost in plain sight.

Let me repeat a principle I noted above, because I think it is important here. These are not just the treasures of any particular institution, culture, or country. They are treasures of world culture. They are important for all of us. And so objects such as this vase belong just as much in Minneapolis as they do in Italy, where it came from the ground and was mostly likely made all those centuries ago. Indeed, they may carry more value here rather than there.

Because these are matters of world culture, not just national culture, I find the trend for various nations to call for treasures in some of the world’s great museums to be returned is a disturbing one. The direction is backward, for it tends toward greater concentration rather than greater distribution of the world’s art and ancient treasures. Most certainly, no no nation should be deprived of its own cultural heritage and history. It would be totally inappropriate to largely empty Greece, Italy, Egypt, China, or any other nation of its most significant antiquities and art. But the current, and problematic, ethos is quite the opposite, as it would tend to result in emptying much of the world of prime examples of art, especially ancient art. Nations and cultures should be able to have important and extensive collections of their own artistic and cultural heritage. Yet, contrary to the implication of claims for specific pieces of art by various nations, the distribution of these treasures in various places is actually a good thing. It should be recognized as valuable and good that people the world over can learn about and participate in the beauty of our shared human culture in the form of the unique expression of various cultures and periods. Such distribution is also about safeguarding our common heritage and the uniqueness of particular cultures, so that unfortunate (and especially currently unforeseen) events do not bring our access to so many treasures of this or that culture to a tragic end.

Lastly, it seems to me that the means and tactics that Italy, Egypt and others end up using to obtain the return of these artifacts are highly questionable as well. Italy did not bring the matter of the krater in Minneapolis to the MIA’s attention. It was the Institute that initiated the investigation of the vase. But we’ve seen Egypt sever ties with institutions (such as the Louvre) or threaten cutting off institutions, as a means of leveraging the transfer of items it wants. In less severe form, the country seeking an artifact’s return most certainly leverages the situation with suggestions of looming, black ethical clouds hovering over the museum or their collection. This may have legal sanction for various, even good, reasons, but is the tactic not without it’s own questions and ethical problems, especially when it ends up extracting artifacts, originally obtained appropriate by the standards of the time, from museums without compensation? Is that not a form of looting, too?

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts obtained the vase, which is a key part of its small collection in ancient Mediterranean art, in good faith under the standards of the time. It is unfortunate that the object was apparently looted, but the Institute is not accused of having anything to do with that illegality. What harm has been done, has already been done. That harm is neither continued by allowing the vase to stay where it has been, nor is it mitigated by removing it from the collection it is in. So far, things may be even. But then considering important values connected to a shared world heritage, art, education, and the very purpose and existence of museums, the balance for me turns against the return of an artifact in this case. I am very much disappointed in the decision of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts to voluntarily return the volute krater. Rather than further an ethical standard, I think it undercuts the values such museums should be upholding. Be clear, this isn’t a value that says looting of archeological sites doesn’t matter, for it most certainly does, but museums such as the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and many others around the world, should be holding fast to important values weighing heavily for the accessibility of art and culture around the world in all of our lives.

Leave a Reply