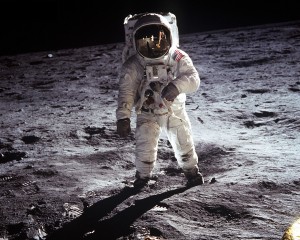

Forty years have now elapsed since two from amongst our human species landed on the moon. About six and a half hours latter, Neil Armstrong set foot on the lunar surface. The collective effort of NASA, the many scientists and engineers, and the astronauts themselves was perhaps our greatest human achievement, or at least the greatest human achievement of modern times. This has no doubt been said many times in the days leading up to this anniversary, and be said even more today, so perhaps it’s a bit of a cliché. Cliché or not, I also think it’s true. I have long watched footage of the launch of Apollo 11, the landing on the moon, and the moon walk with interest and awe. A part of me wishes I had been alive and old enough to remember these events for myself; to have been amongst the millions who sat glued to their television sets that July evening.

Forty years have now elapsed since two from amongst our human species landed on the moon. About six and a half hours latter, Neil Armstrong set foot on the lunar surface. The collective effort of NASA, the many scientists and engineers, and the astronauts themselves was perhaps our greatest human achievement, or at least the greatest human achievement of modern times. This has no doubt been said many times in the days leading up to this anniversary, and be said even more today, so perhaps it’s a bit of a cliché. Cliché or not, I also think it’s true. I have long watched footage of the launch of Apollo 11, the landing on the moon, and the moon walk with interest and awe. A part of me wishes I had been alive and old enough to remember these events for myself; to have been amongst the millions who sat glued to their television sets that July evening.

In so many ways, we have moved forward technologically and scientifically since then. There is so much more science we could do on the moon today, or on Mars. Materials science has seen great progress, which should help us in making vehicles to go back or go on to Mars. And the efforts to make this mission, and all the Apollo missions, work were largely responsible for some great pushes forward in electronics and many other technologies, especially the miniaturization of computers. The computer on which I write this post, and on which you are reading it, is vastly more powerful than the computers on board the command module and LEM. Indeed, your computer and mine probably have more computing power and capacity than was available to the whole of NASA at the time Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong walked on the lunar surface. They certainly are much more speedy. And, yet, we are currently incapable of going back to the moon.

Our incapacity is not merely that we currently lack rockets and space vehicles powerful enough and with the right capabilities to reach and land on the moon, much less Mars. And it isn’t really about the lack of budgets and political will, although those problems (and, yes, they are problems!) also play a part in it. We have actually lost know-how. Even in some of the development for the Space Shuttle successor is necessitating that we re-learn how to do certain things. I’ve read that NASA engineers have been rifling through surplus depots, old warehouses, and museums looking for components from the mighty Saturn V and other components of these missions, hoping to be able to learn from them what they need to know for today’s and tomorrow’s space program engineering challenges. We may have come quite a ways since July 20, 1969, but we’ve also fallen behind that time. If in just forty years this kind of cloud can be drawn over our knowledge of past achievements, no wonder there are so many aspects of human history over which a thickly opaque veil is drawn.

Our incapacity is not merely that we currently lack rockets and space vehicles powerful enough and with the right capabilities to reach and land on the moon, much less Mars. And it isn’t really about the lack of budgets and political will, although those problems (and, yes, they are problems!) also play a part in it. We have actually lost know-how. Even in some of the development for the Space Shuttle successor is necessitating that we re-learn how to do certain things. I’ve read that NASA engineers have been rifling through surplus depots, old warehouses, and museums looking for components from the mighty Saturn V and other components of these missions, hoping to be able to learn from them what they need to know for today’s and tomorrow’s space program engineering challenges. We may have come quite a ways since July 20, 1969, but we’ve also fallen behind that time. If in just forty years this kind of cloud can be drawn over our knowledge of past achievements, no wonder there are so many aspects of human history over which a thickly opaque veil is drawn.

Not only have we lost history and engineering knowledge and practice, but I think we’ve lost something of ourselves and our humanity in that time. It seems that we’ve become rather content to let things coast and to keep our collective mind on things a bit closer to the ground. Sometimes this is needed, certainly, but with it comes a loss of large scale visionary work, inspiring achievement, the thirst for exploration, and the hunger for knowledge. In some ways, we’ve been hijacked by petty concerns and self-interest (and mostly of the unenlightened kind) and are so very lacking in imagination. We desperately need to regain some of that same spirit, yearning after exploration, and pursuit of knowledge that worked in the early space program through the Apollo program.

Science has become so un-cool since this history event whose anniversary we observe today. It’s luster has been lost for some reason. Perhaps it was placed too much on a pedestal back then, and perhaps that pedestal was heavily motivated by Cold War concerns. But, in some ways, many of those who busy themselves with bashing an educational system for not reaching high enough standards, are really creating a huge distraction from some of the real issues of education, especially science and mathematics education. (And maybe it’s little wonder that some of these people are really seeking to distract, because they also often do what they can to undermine science in the supposed name of “values”.) Whatever reforms we do need in our educational system, one thing often remains unspoken: the need to once again actually value the pursuit of science and mathematics, encourage it in young people, and re-awaken public interest and value in science and technology.

I find this Apollo 11 anniversary exciting, and yet I also find it bittersweet because of what we have lost and what we are now incapable of doing. The Apollo mission captured public attention. It fired the imaginations of both young and old. All of this was deemed to be of value. It’s time we return to those values. It’s time we returned to meaningful space exploration. It’s time we once again reach for the moon and beyond, especially for Mars. And let’s work to make such a mission once again fire the imaginations of both young and old alike. Let’s not let the foot prints left on the moon during those years of Apollo missions be the first and the last we humans leave on another world.

I find this Apollo 11 anniversary exciting, and yet I also find it bittersweet because of what we have lost and what we are now incapable of doing. The Apollo mission captured public attention. It fired the imaginations of both young and old. All of this was deemed to be of value. It’s time we return to those values. It’s time we returned to meaningful space exploration. It’s time we once again reach for the moon and beyond, especially for Mars. And let’s work to make such a mission once again fire the imaginations of both young and old alike. Let’s not let the foot prints left on the moon during those years of Apollo missions be the first and the last we humans leave on another world.

We chose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.

—John F. Kennedy, September 12, 1962

Leave a Reply